Log in

Statistics

We have 484 registered usersThe newest registered user is mark5

Our users have posted a total of 48862 messages in 7215 subjects

THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT

CLICK ON ANY OF THESE LINKS TO FIND OUR EXTREME ENTERTAINMENT

UPDATED :

71 WGT TUTORIALS & 32 YOUNG46 TUTORIALS

CLICK HERE TO SEE OVER 100 YOUTUBE VIDEO TUTORIALS . FROM WGTers , WGT & YOUNG46 FORUM UPDATE

TO THE MANY WELCOME GUESTS . THIS FORUM IS NO LONGER A COUNTRY CLUB WEBSITE FOR A WGT COUNTRY CLUB . PLEASE FEEL FREE TO READ THE FORUMS.

THERE ARE MANY TOPICS OF INTEREST . OR NOT . THIS WEBSITE IS AN INFORMATION AND ENTERTAINMENT WEBSITE ONLY .

MUCH OF THE CONTENT IS ARCHIVES OF PURPOSES PAST .

THERE ARE SOME MORE CURRENT TOPICS .

REGISTRATION IS NOT NECESSARY TO READ THROUGHOUT .

REGISTRATION IS EASY AND FREE . THIS IS AN AD FREE WEBSITE . NOTHING IS EVER REQUESTED FROM REGISTERED MEMBERS .

REGISTRATION ENABLES COMMENTING ON TOPICS . POSTING NEW TOPICS . FULL ACCESS TO THE WEBSITE IMAGE HOST . WHICH IS A VERY COMPLETE AND CONVENIENT TOOL .

PLEASE ENJOY .

TIER & AVERAGE REQUIREMENTS

BASIC LEVEL AND AVERAGE REQUIREMENTS , AND SATURATION

WHILE YOUR HERE

WHILE YOUR HERE :

CHECK OUT THE INCREDIBLE PHOTOGRAPHY IN

MY SERIES

THIS USED TO BE THE HOME OF OUR WORLD CLOCK . WHICH CAN NOW BE FOUND IN ITS OWN FORUM ON THE MAIN PAGE ..

THERE ARE MORE WORLD CLOCKS INSIDE HERE .

WORLD CLOCK

FB Like

ON THIS DAY 3 18 2023

Page 1 of 1

ON THIS DAY 3 18 2023

ON THIS DAY 3 18 2023

This Day in History: March 18

art theft

crime

art theft, criminal activity involving the theft of art or cultural property, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, and other objets d’art.

The perceived value of a given work, be it financial, artistic, or cultural—or some combination of those factors—is frequently the motive for art theft. Because of the portability of works such as paintings, as well as their concentration in museums or private collections, there have been persistent examples of major thefts of art. Because of the widespread media coverage that such heists often generate, the public is likely to be aware of thefts of this scale. Such was the case with the theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. The two-year search for the missing masterpiece granted the Mona Lisa an unmatched celebrity, elevating it immensely in the popular consciousness. Thefts among private galleries and individual collectors may not be as widely reported, but taken as a whole, they represent a significant part of a criminal activity that spans the globe. In the early 21st century, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation estimated that art valued at $4 billion to $6 billion was stolen worldwide each year.

When the movement of illegal art is examined as a criminal market, it is apparent that it differs from markets for goods that are illegal to produce, such as counterfeit money or illegal drugs. To realize their full value, works of stolen art must move through some portal to the legitimate market—thus, the movement of illegal art often will have a half-illicit, half-licit character. Because there are relatively narrow portals to the secondary art market, a number of preventive steps can be taken to restrict the movement of illegal art. These might include increasing the efficiency of theft registers, increasing the size and reach of catalogs of the known works of established artists, and creating action committees among commercial dealers’ associations that can act when rumours begin to circulate about the presence of stolen works in the market. Even one theft can cause enormous damage. Ultimately, vigilance of dealers and consumers will provide one of the major disincentives for those considering their possible gains through the theft of art.

One puzzle about art theft is that it often appears to be a crime with no easy rewards for the perpetrator. For most thieves, in fact, art is not a commodity of choice, either because they do not have the knowledge to negotiate the movement of art onto the market or because they seek ready cash, and the disposition of art, especially for anything close to its market value, may take many months. Another complication is the existence of registers of stolen works, such as the Art Loss Register, which further decreases the probability of the successful disposal of stolen art. Collectors or dealers who experience a theft notify these registers of their loss immediately. As a consequence, it becomes exceptionally difficult to move a stolen work of any stature onto the legitimate market, because it would be routine for major dealers and the largest auction houses to consult theft registers before considering handling a work, especially a major one.

One result of the growing difficulties in the disposal of stolen art is that many works simply disappear after they have been stolen. Works by Vermeer, Manet, and Rembrandt stolen from the Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, for example, have not been recovered. There are three major possibilities concerning the status of such works: (1) they may find their way into the hidden collections of individuals, known in the art trade as “gloaters,” who are willing to take the risks of owning works of art that they know to be stolen; (2) the thieves may hold on to the works in the hope that it might be possible to move the works onto the market after the notoriety of the theft has died down; and (3) the perpetrators may destroy the works when they realize how difficult it is to sell stolen art and then become aware of the consequences of being caught with the works in their possession.

Nazi art theft

There are other distinctive forms of art theft. During war, lawlessness may give rise to widespread looting. Such was the case when thousands of priceless artifacts and antiquities were taken from museums and archaeological sites during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. War can also provide cover for more systematic art theft, as in the seizure of thousands of major works of art by the Nazis during World War II. In addition to so-called “degenerate art” confiscated by the Nazis in the years prior to the war, German armies plundered works from museums and private collections as they advanced across Europe. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Allied soldiers discovered large caches of stolen works hidden in salt mines, but significant pieces, such as the Amber Room, a collection of gilded and bejeweled wall panels taken from the Catherine Palace in Pushkin, Russia, have never been recovered. Works stolen by Nazis have been found in major international collections, including leading museums, and families of the original victims continue to pursue legal action to regain ownership of these works. In 2011 German police uncovered a stash of some 1,500 paintings, with an estimated value of $1 billion, in a cluttered nondescript apartment in Munich. The collection, which included works by “degenerate” artists such as Picasso, Matisse, and Chagall, had been confiscated by the Nazis and was considered lost in the postwar era.

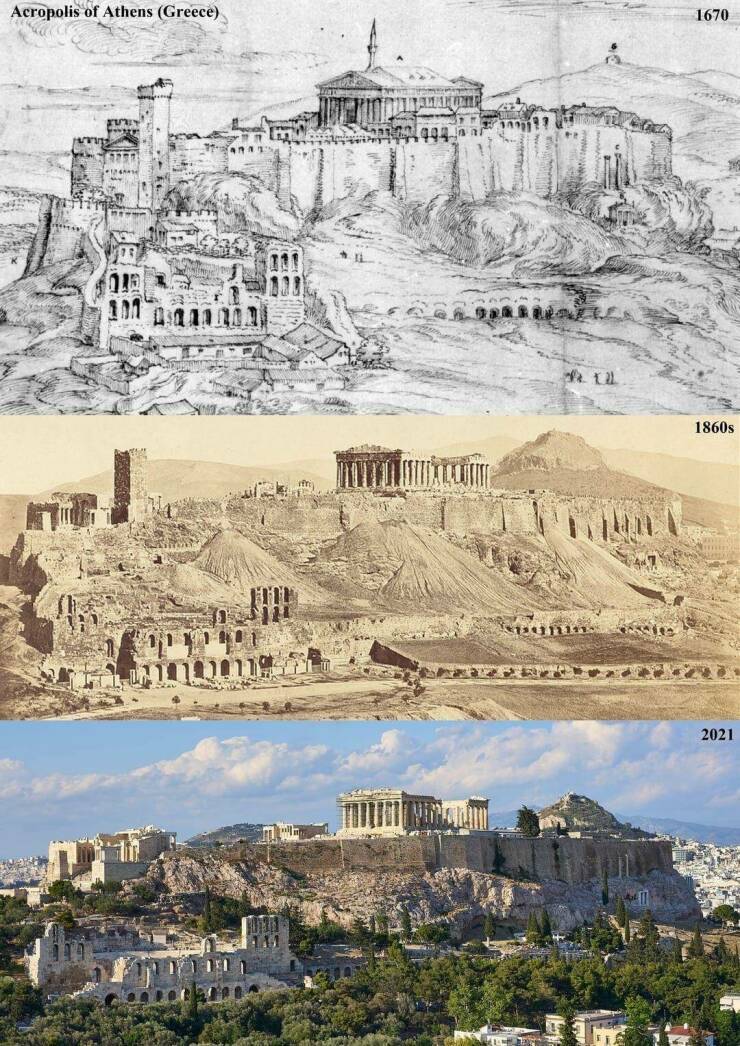

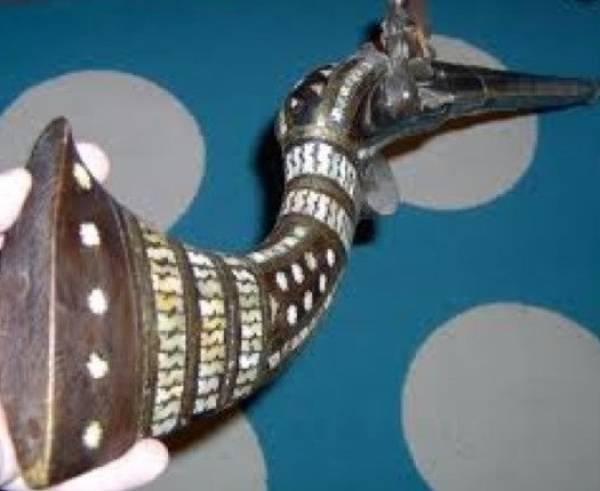

A somewhat different form of theft involves the plunder or removal of cultural or archaeological treasures, often from countries in the developing world. Such treasures are then sold on the international market or displayed in museums. The latter practice is commonly known as elginism, after Thomas Bruce, 7th earl of Elgin, a British ambassador who acquired a collection of Greek sculptures that has subsequently become known as the Elgin Marbles. Such cases demonstrate that there may be complex moral and legal issues that arise when stolen art passes on to the legitimate art market and into the hands of buyers who purchase in good faith.

Featured Event

art theft

crime

art theft, criminal activity involving the theft of art or cultural property, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, and other objets d’art.

The perceived value of a given work, be it financial, artistic, or cultural—or some combination of those factors—is frequently the motive for art theft. Because of the portability of works such as paintings, as well as their concentration in museums or private collections, there have been persistent examples of major thefts of art. Because of the widespread media coverage that such heists often generate, the public is likely to be aware of thefts of this scale. Such was the case with the theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. The two-year search for the missing masterpiece granted the Mona Lisa an unmatched celebrity, elevating it immensely in the popular consciousness. Thefts among private galleries and individual collectors may not be as widely reported, but taken as a whole, they represent a significant part of a criminal activity that spans the globe. In the early 21st century, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation estimated that art valued at $4 billion to $6 billion was stolen worldwide each year.

When the movement of illegal art is examined as a criminal market, it is apparent that it differs from markets for goods that are illegal to produce, such as counterfeit money or illegal drugs. To realize their full value, works of stolen art must move through some portal to the legitimate market—thus, the movement of illegal art often will have a half-illicit, half-licit character. Because there are relatively narrow portals to the secondary art market, a number of preventive steps can be taken to restrict the movement of illegal art. These might include increasing the efficiency of theft registers, increasing the size and reach of catalogs of the known works of established artists, and creating action committees among commercial dealers’ associations that can act when rumours begin to circulate about the presence of stolen works in the market. Even one theft can cause enormous damage. Ultimately, vigilance of dealers and consumers will provide one of the major disincentives for those considering their possible gains through the theft of art.

One puzzle about art theft is that it often appears to be a crime with no easy rewards for the perpetrator. For most thieves, in fact, art is not a commodity of choice, either because they do not have the knowledge to negotiate the movement of art onto the market or because they seek ready cash, and the disposition of art, especially for anything close to its market value, may take many months. Another complication is the existence of registers of stolen works, such as the Art Loss Register, which further decreases the probability of the successful disposal of stolen art. Collectors or dealers who experience a theft notify these registers of their loss immediately. As a consequence, it becomes exceptionally difficult to move a stolen work of any stature onto the legitimate market, because it would be routine for major dealers and the largest auction houses to consult theft registers before considering handling a work, especially a major one.

One result of the growing difficulties in the disposal of stolen art is that many works simply disappear after they have been stolen. Works by Vermeer, Manet, and Rembrandt stolen from the Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, for example, have not been recovered. There are three major possibilities concerning the status of such works: (1) they may find their way into the hidden collections of individuals, known in the art trade as “gloaters,” who are willing to take the risks of owning works of art that they know to be stolen; (2) the thieves may hold on to the works in the hope that it might be possible to move the works onto the market after the notoriety of the theft has died down; and (3) the perpetrators may destroy the works when they realize how difficult it is to sell stolen art and then become aware of the consequences of being caught with the works in their possession.

Nazi art theft

There are other distinctive forms of art theft. During war, lawlessness may give rise to widespread looting. Such was the case when thousands of priceless artifacts and antiquities were taken from museums and archaeological sites during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. War can also provide cover for more systematic art theft, as in the seizure of thousands of major works of art by the Nazis during World War II. In addition to so-called “degenerate art” confiscated by the Nazis in the years prior to the war, German armies plundered works from museums and private collections as they advanced across Europe. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Allied soldiers discovered large caches of stolen works hidden in salt mines, but significant pieces, such as the Amber Room, a collection of gilded and bejeweled wall panels taken from the Catherine Palace in Pushkin, Russia, have never been recovered. Works stolen by Nazis have been found in major international collections, including leading museums, and families of the original victims continue to pursue legal action to regain ownership of these works. In 2011 German police uncovered a stash of some 1,500 paintings, with an estimated value of $1 billion, in a cluttered nondescript apartment in Munich. The collection, which included works by “degenerate” artists such as Picasso, Matisse, and Chagall, had been confiscated by the Nazis and was considered lost in the postwar era.

A somewhat different form of theft involves the plunder or removal of cultural or archaeological treasures, often from countries in the developing world. Such treasures are then sold on the international market or displayed in museums. The latter practice is commonly known as elginism, after Thomas Bruce, 7th earl of Elgin, a British ambassador who acquired a collection of Greek sculptures that has subsequently become known as the Elgin Marbles. Such cases demonstrate that there may be complex moral and legal issues that arise when stolen art passes on to the legitimate art market and into the hands of buyers who purchase in good faith.

FEATURED BIO

FEATURED BIO

Queen Latifah

American musician and actress

Queen Latifah, byname of Dana Elaine Owens, (born March 18, 1970, Newark, New Jersey, U.S.), American musician and actress whose success in the late 1980s launched a wave of female rappers and helped redefine the traditionally male genre. She later became a notable actress.

Owens was given the nickname Latifah (Arabic for “delicate” or “sensitive”) as a child and later adopted the moniker Queen Latifah. In high school she was a member of the all-female rap group Ladies Fresh, and, while studying communications at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, she recorded a demo tape that caught the attention of Tommy Boy Records, which signed the 18-year-old. In 1988 she released her first single, “Wrath of My Madness,” and the following year her debut album, All Hail the Queen, appeared. Propelled by diverse styles—including soul, reggae, and dance—and feminist themes, it earned positive reviews and attracted a wide audience. Soon after, Queen Latifah founded her own management company. Her second album, Nature of a Sista (1991), however, failed to match the sales of her previous effort, and Tommy Boy did not re-sign her. After signing with Motown Records, she released Black Reign in 1993. The album was a critical and commercial success, and the single “U.N.I.T.Y.,” which decried sexism and violence against women, earned a Grammy Award.

In 1991 Queen Latifah made her big-screen debut in Jungle Fever, and after several television appearances she was signed in 1993 to costar in the series Living Single. The show ended in 1998, and later that year Queen Latifah played a jazz singer in the film Living Out Loud. Her commanding screen presence brought roles in more movies, including The Bone Collector (1999) and Brown Sugar (2002). In 1999 she began a two-year stint of hosting her own daytime talk show, and that year she published Ladies First: Revelations of a Strong Woman (written with Karen Hunter).

Queen Latifah’s prominence in Hollywood was cemented in 2003, when she received an Academy Award nomination (best supporting actress) for her portrayal of Matron Mama Morton in the big-screen adaptation (2002) of the stage musical Chicago. The film was followed by the comedies Bringing Down the House (2003), which Queen Latifah both starred in and produced, Barbershop 2: Back in Business (2004), Beauty Shop (2005), and Last Holiday (2006). She again brought her musical background to the screen for her role as Motormouth Maybelle in the film Hairspray (2007), a remake of the stage musical.

In 2008 Queen Latifah starred in The Secret Life of Bees, a drama about a white girl taken in by a family of beekeeping African American women in 1960s-era South Carolina. She later appeared in the romantic comedies Valentine’s Day (2010), Just Wright (2010), and The Dilemma (2011). In Joyful Noise (2012) Queen Latifah starred opposite Dolly Parton as the director of a competitive church gospel choir. She followed that performance with a role as a Southern matriarch in the TV movie Steel Magnolias (2012), which, in contrast to the 1980s stage and film productions on which it was based, featured a predominantly African American cast. Her other notable television movies included Life Support (2007), about a former addict turned AIDS activist; Bessie (2015), in which she starred as the blues singer Bessie Smith; and The Wiz Live! (2015), based on the Broadway musical.

Queen Latifah’s later TV work included the series Star (2016–19), about three female singers hoping to become superstars, and The Equalizer (2021– ), in which she starred as a former CIA agent who becomes a vigilante. She also was cast in the special The Little Mermaid Live! (2019), and she played Hattie McDaniel in the miniseries Hollywood (2020). During this time Queen Latifah continued to appear on the big screen. In 2017 she starred in the comedy Girls Trip, and she later was featured in the family film The Tiger Rising (2022). In addition, her voice was featured in several movies, including four installments (2006, 2009, 2012, 2016) of the animated Ice Age series.

Throughout her acting career, Queen Latifah continued to record. Her other albums included The Dana Owens Album (2004) and Trav’lin’ Light (2007), collections of jazz and pop standards that showcased her strong singing voice, and Persona (2009), an eclectic return to hip-hop. In 2013–15 she hosted another daytime talk show, The Queen Latifah Show.

American musician and actress

Queen Latifah, byname of Dana Elaine Owens, (born March 18, 1970, Newark, New Jersey, U.S.), American musician and actress whose success in the late 1980s launched a wave of female rappers and helped redefine the traditionally male genre. She later became a notable actress.

Owens was given the nickname Latifah (Arabic for “delicate” or “sensitive”) as a child and later adopted the moniker Queen Latifah. In high school she was a member of the all-female rap group Ladies Fresh, and, while studying communications at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, she recorded a demo tape that caught the attention of Tommy Boy Records, which signed the 18-year-old. In 1988 she released her first single, “Wrath of My Madness,” and the following year her debut album, All Hail the Queen, appeared. Propelled by diverse styles—including soul, reggae, and dance—and feminist themes, it earned positive reviews and attracted a wide audience. Soon after, Queen Latifah founded her own management company. Her second album, Nature of a Sista (1991), however, failed to match the sales of her previous effort, and Tommy Boy did not re-sign her. After signing with Motown Records, she released Black Reign in 1993. The album was a critical and commercial success, and the single “U.N.I.T.Y.,” which decried sexism and violence against women, earned a Grammy Award.

In 1991 Queen Latifah made her big-screen debut in Jungle Fever, and after several television appearances she was signed in 1993 to costar in the series Living Single. The show ended in 1998, and later that year Queen Latifah played a jazz singer in the film Living Out Loud. Her commanding screen presence brought roles in more movies, including The Bone Collector (1999) and Brown Sugar (2002). In 1999 she began a two-year stint of hosting her own daytime talk show, and that year she published Ladies First: Revelations of a Strong Woman (written with Karen Hunter).

Queen Latifah’s prominence in Hollywood was cemented in 2003, when she received an Academy Award nomination (best supporting actress) for her portrayal of Matron Mama Morton in the big-screen adaptation (2002) of the stage musical Chicago. The film was followed by the comedies Bringing Down the House (2003), which Queen Latifah both starred in and produced, Barbershop 2: Back in Business (2004), Beauty Shop (2005), and Last Holiday (2006). She again brought her musical background to the screen for her role as Motormouth Maybelle in the film Hairspray (2007), a remake of the stage musical.

In 2008 Queen Latifah starred in The Secret Life of Bees, a drama about a white girl taken in by a family of beekeeping African American women in 1960s-era South Carolina. She later appeared in the romantic comedies Valentine’s Day (2010), Just Wright (2010), and The Dilemma (2011). In Joyful Noise (2012) Queen Latifah starred opposite Dolly Parton as the director of a competitive church gospel choir. She followed that performance with a role as a Southern matriarch in the TV movie Steel Magnolias (2012), which, in contrast to the 1980s stage and film productions on which it was based, featured a predominantly African American cast. Her other notable television movies included Life Support (2007), about a former addict turned AIDS activist; Bessie (2015), in which she starred as the blues singer Bessie Smith; and The Wiz Live! (2015), based on the Broadway musical.

Queen Latifah’s later TV work included the series Star (2016–19), about three female singers hoping to become superstars, and The Equalizer (2021– ), in which she starred as a former CIA agent who becomes a vigilante. She also was cast in the special The Little Mermaid Live! (2019), and she played Hattie McDaniel in the miniseries Hollywood (2020). During this time Queen Latifah continued to appear on the big screen. In 2017 she starred in the comedy Girls Trip, and she later was featured in the family film The Tiger Rising (2022). In addition, her voice was featured in several movies, including four installments (2006, 2009, 2012, 2016) of the animated Ice Age series.

Throughout her acting career, Queen Latifah continued to record. Her other albums included The Dana Owens Album (2004) and Trav’lin’ Light (2007), collections of jazz and pop standards that showcased her strong singing voice, and Persona (2009), an eclectic return to hip-hop. In 2013–15 she hosted another daytime talk show, The Queen Latifah Show.

Similar topics

Similar topics» ON THIS DAY 3 22 2023

» ON THIS DAY 4 22 2023

» ON THIS DAY 5 8 2023

» ON THIS DAY 2 28 2023

» ON THIS DAY 3 8 2023

» ON THIS DAY 4 22 2023

» ON THIS DAY 5 8 2023

» ON THIS DAY 2 28 2023

» ON THIS DAY 3 8 2023

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

Events

Events

» *POPULAR CONTENTS* Valley of the SUN Official Newsletter

» Disneyland vacation

» WGT POETRY , QUOTES , MOMENTS , & MORE

» Word Genius Word of the day * Spindrift *

» Tales of Miurag #3 in Paperback Patreon Story in December!

» Download WhatsApp

» WORD DAILY Word of the Day: * Saponaceous *

» Word Genius Word of the day * Infracaninophile *

» THE TRUMP DUMP .....

» INTERESTING FACTS * How do astronauts vote from space? *

» WWE Crown Jewel is almost here! Don't miss the action LIVE today only on Peacock!

» NEW GUEST COUNTER

» Merriam - Webster Word of the day * ‘Deadhead’ *

» WWE Universe: Your Crown Jewel Broadcast Schedule has arrived!